Theoretical Framework

TRAUMA AND ADVERSITY

We have students in our schools who have great difficulty behaving. Sometimes they have meltdowns that come “out of the blue”. These students are unpredictable and as a result have difficulty with social interactions. It seems to take very little to provoke them into acting in ways that hurt other students.

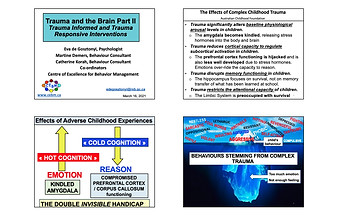

It has been confirmed that students who have had adverse childhood experiences such as emotional and physical neglect and abuse are significantly affected by these experiences. The effects often manifest in the form of challenging or seemingly maladaptive behaviours but are now known to be the result of alterations in the brain chemistry and structure caused by their experiences.

These students often have an overactivated amygdala, which causes an intensive and swift emotional response to perceived threat, and an underactive prefrontal cortex which affects their ability to modulate their emotional responses. Responses to trauma are complex and pervasive. Some students lash out, others become “oppositional”, others try to control everyone and others become anxious or withdraw. Many exhibit most or all of these behaviours.

No matter what the behaviour, the adults responding to these students must keep in mind that these students have a double invisible handicap. Recovery is possible and the extent of the damage caused by these adverse childhood experiences can be mitigated by adults in the child’s life. If the painful emotions are acknowledged and given permission and space to flow through, the effects of trauma are less pervasive. However, this requires that the adults accept that it is their responsibility to find a way to reassure the student that he/she will continue to be cared for.

DOWNLOADABLE DOCUMENTS:

ALTERNATIVE TO CONVENTIONAL DISCIPLINE:

EDITORIAL: When Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACES) Underlie Problem Behaviors

Mona Delahooke

Four-year-old Wyatt was struggling in preschool, suddenly defying directions, and demanding more attention than usual. Nap time became a particular challenge. He would slither on the floor, trying to avoid his cot, in the process disturbing others trying to sleep. Frustrated, his teachers would ask him to stop bothering others, giving him few minutes to comply. When Wyatt didn’t comply, a teacher or helper would try physically directing him back to his cot. Usually, that made him panic and kick anyone close by. When he kicked, a helper restrained him, often causing him to kick and fight back even harder. Eventually, Wyatt was asked to leave his preschool.

Childhood Trauma: Understanding Behavioral Challenges as Survival Instincts

Mona Delahooke

This is a blog post I never wanted to write. In light of the tidal wave of neuroscience research, I had hoped that by now the fields of education, mental health and juvenile justice would change the way they view and support children and teens exposed to trauma. That hasn’t happened yet. And while I’m hesitant to add to caregivers’ worries or to offend respected colleagues, I feel it’s important to explain why certain approaches to behavioral challenges may be harmful to vulnerable children.

Why We Misunderstand Traumatized Children’s Behavioral Challenges and How We Can Do Better

Mona Delahooke

By the time he turned eleven, “Luke” had consistently displayed such challenging behavior that he had been kicked out of four foster homes. Finally, a social worker placed him with parents who had been trained in a program that focused on behavior management. That placement was also unsuccessful, and he landed in a residential school for youth who were severely emotionally disturbed.

Roisleen Todd - Edutopia

While teachers are not social workers, just saying the right things to a student suffering from trauma can make a big difference. Our students are carrying a lot with them as they enter our classrooms each day—always, but especially right now. As educators, we lead with love, and we often see ourselves as (and we often are) primary sources of support for students not only in academics, but in all areas of students’ lives.

Building Confidence and Resilience Through the Arts

Edutopia

How can schools create a healing environment in their classrooms—with a trauma-informed lens? Students in the small town of Glen Ellen, like many in California, were affected first by wildfires and then by the social isolation of the pandemic. Teachers needed a way to build students’ resilience and self-regulation skills back up. Their solution? Partnering with—and getting training from—local arts organizations, including Kimzin Creative and Sonoma Community Center, to help students learn how to express themselves and collaborate with each other again.